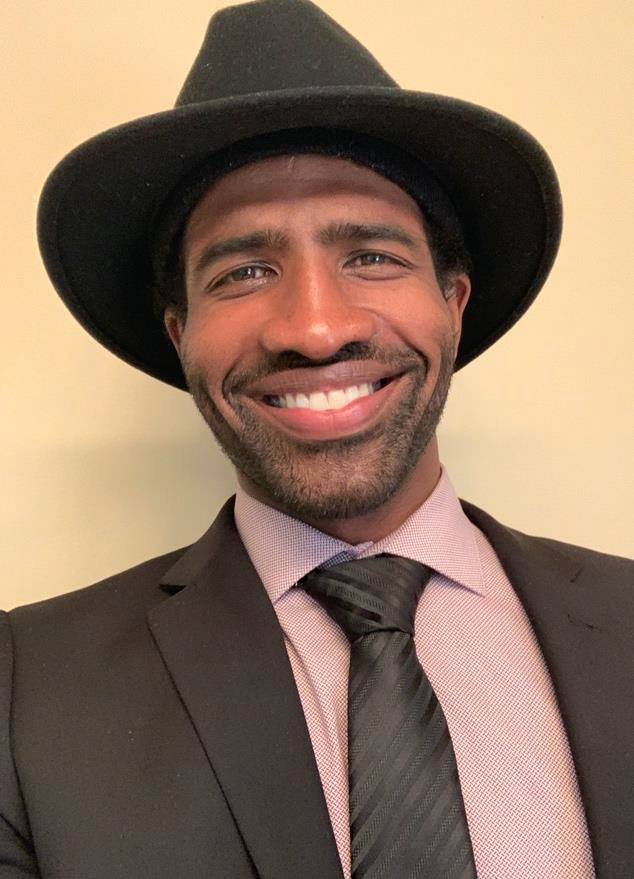

By: Omar Pryce

For so many students who are justice involved and/or system impacted, reintegrating into society with the albatross of a criminal record around one’s neck can be daunting at best. Social work graduate students who have been formerly incarcerated have even more hurdles to overcome with reduced field placement options and future licensure requirements that can rub a rehabilitated person’s face in the mistakes of their past. The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) core values of social justice and the dignity and worth of the person need to be fully realized amongst this paraprofessional and professional demographic.

This issue hits home with me. At the age of 19, I was arrested, and eventually convicted and sentenced to 24 years in prison for a robbery. Though there were no injuries of any kind reported and this was my first time encountering the adult justice system, the People had decided that my nature was so irredeemable that only a quarter-century in prison could afford me a second chance at life.

I was already a shattered individual; fragmented pieces held together by tenuous strands of ego and hyper masculinity in a futile attempt to maintain control over systemic forces seemingly beyond my control. What was life to me but a charade, a socially constructed prison that would ultimately, brick by brick, build its tangible manifestation. Mass incarceration was more than a dramatic narrative and rallying cry for social justice warriors. It engulfed me, obfuscating any light within me until I was a blotted stain, charred ashes of wasted potential. I wanted to scream, but perhaps, that would bring scrutiny from the armed sentry in the gun tower. I perfected anonymity, a fitting talent of a voiceless number out of tune with the outside world.

Rehabilitation? That was somewhere perched high upon a Maslowian summit that couldn’t be imagined at the time. Survival was the order of the day. To be sure, I encountered social workers along the way. While I do not want to discredit any of their capabilities or intentions, they were perceived as “others”, as agents of the State. How could I open up and be receptive to change through interactions with people I felt had no insight as to what it meant to be oppressed and struggle against a system that facilitates and benefits from my inability to exorcise my own demons? I recollected my adolescent experiences with social workers, who seemingly latched onto candid statements that squeezed through the cracks of my juvenile bravado to provide fodder for probation and court systems to use against me. Change was a lonely endeavor achieved through my own study of myself and my relation to the systems I found myself a part of.

Fortunately, the SB 261 Youth Offender Bill went into effect in 2016, and I was afforded the opportunity at early parole in October of 2018. Upon my release from prison, I stumbled across Romarilyn Ralston, another formerly incarcerated person, who also happened to be the program director of Project Rebound at California State University Fullerton. She linked me up with the first college housing in the nation for formerly incarcerated students, the John Irwin Memorial House. Prison provides the opportunity for community college, but a bachelor’s degree was only available to those who could pay for their own tuition. Pell grants are not provided to prisoners. Through the help of family and friends I was able to scrape together the funds to pay for a class here and there as my shackled feet inched towards my bachelor’s degree. While at the John Irwin Memorial House, I finished the 21 remaining units I needed, and an internship, the semester after I paroled. Upon graduating, an application was immediately submitted to the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

During the field placement process, I serendipitously encountered Susan Hess, a clinical assistant professor and regional field faculty member at USC, who had volunteered to give justice-involved students tips on how to present their background during field placement interviews. She also introduced me to the Unchained Scholars student group at USC. Unchained Scholars is the first student group for a graduate social work program designed for justice-involved and system-impacted students. Not only does it provide a safe space where I can feel unburdened by the weight of my past, it facilitates networking, understanding and integration with a broader coalition of social work graduate students, allies and professionals. Unchained Scholars are uniquely positioned to weave a tapestry of trauma into a banner of social justice. Our lived experience brings a level of authenticity, understanding and empathy towards the marginalized populations we come in contact with that can’t be learned from textbooks.

I have been out of prison for a little over 14 months. I now have reason to hope that there will be a time when social work paraprofessionals and professionals appear less as “others” to the diverse populations we serve. I hope through the work of groups like Unchained Scholars, that the Scarlett letter of formerly incarcerated students is not more deeply branded by academic and professional naivete, and an overly interrogative licensure process. With the tides of change, our values must inevitably lead to us being considered as one with other paraprofessional and professional social workers; establishing an inclusive body that strives towards breaking down the barriers of an “other” and creating an US.

Omar Pryce is an MSW candidate at the University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and an ICMS program manager providing services for community members in Los Angeles who are experiencing chronic homelessness and mental health challenges.