By Jason Bloome

A managed long-term support and services (MLTSS) program, which involve capitated payments to managed care organizations (MCOs) to provide care services for members on Medicaid and Medicare, is a tool used by many states, currently 19, to manage healthcare costs and healthcare delivery. States implement MLTSS to save money, increase efficiency, improve quality, integrate care and rebalance care delivery from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) to home and community-based services (HCBS).

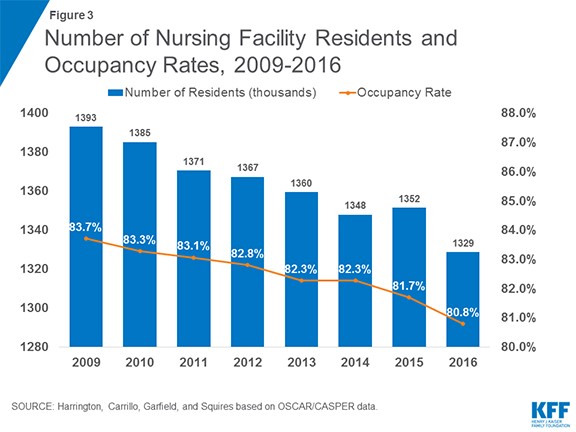

Shifting care from SNFs to HCBS reduces SNF occupancy rates. According to the National Investment Center of Senior Housing and Care, more than 1 out of 5 SNF beds now go unused, approximately 200–300 SNFs close each year and the SNF population has declined from 1.39 million in 2009 to 1.33 million in 2016. Declining SNF occupancy rates is particularly acute in rural America where the closure of even a few local homes results in displaced residents being scattered to the wind and ending up in SNFs far from their hometowns.

Most MLTSS programs include assisted living homes. Surveys indicate most adults would prefer to receive their care at home or in assisted living homes rather than in institutions. According to the federal Government Accounting Office, Medicaid now covers assisted living for more than 330,000 people. A federal program called Money Follows the Person transitioned 75,000 people out of SNFs back into the community.

As MLTSS programs mature, SNF diversion/transition to assisted living will accelerate, fueled in part by large cost savings for MCOs. In California, a state with one of the largest SNF populations, AARP/SCAN estimates at least 10,000 SNF patients (1 out of 10) on long-term care could reside safely in assisted living homes. The number of long-term SNF residents who do not need to be there is most likely much higher since most do not have tracheotomies, ventilators and g-tubes and, instead, have custodial care needs identical to residents in private-paid assisted living homes. Shifting care delivery to assisted living for tens of thousands of SNF residents translates to millions of Medicaid savings each year.

The growth of Medicare Advantage plans (which cover more than 1/3 of all Medicare beneficiaries) also contributes to the decline in SNF censuses when companies offering those plans manage and limit the number of post-hospitalization SNF Medicare days. Medicare Advantage plans also reduce expenses by providing members with enhanced benefits to keep them at home as long as possible (e.g., importing home health services) in order to avoid costly hospital and SNF stays.

Federal penalties that penalize hospitals for excessive readmissions (according to Medicare, 1 out of every 5 seniors discharged from hospitals is readmitted within one month of discharge) also contribute to fewer short-term SNF stays. According to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), more than 2,599 hospitals (82% of participants) received penalties in 2019. Some hospitals seeking to avoid penalties classify incoming patients as “in observation” instead of admitting them. Even though “in observation” patients might be in the hospital for a few days, since they are considered outpatient they are not eligible for Medicare-funded SNF days.

In 2019, CMS increased the scrutiny of SNF staffing levels to use evidenced-based statistics instead of SNF self-reporting. Hiring new staff, in order to be compliant with mandated staffing levels, raises SNF operating expenses and, when censuses are low, impedes its ability to keep its doors open. As many states in the nation raise minimum wage, SNF operators are also forced to increase wages or risk losing their workers to jobs that pay more money, are easier and physically less demanding.

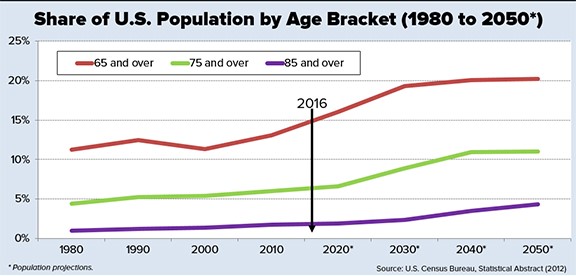

The SNF industry is responding to declining SNF occupancy rates by opening up home health agencies and pharmacies, accepting sicker patients (e.g., on ventilators) at higher rates and going after high-paying Medicare rather than low-paying Medicaid patients. In chasing healthcare dollars that increasingly go to HCBS, many operators are also considering ways of converting SNF buildings to assisted living homes. They stand to benefit when the demand for assisted living outpaces the supply and looming on the horizon is a silver tsunami with 74 million baby boomers who, one day, will require long-term care.

Feeling the pinch of declining censuses, the SNF industry continues to lobby for higher Medicare and Medicaid payments while interest groups, including the Center for Medicare Advocacy, insist that before receiving more public dollars there should be increased oversight of SNF payments, increased fines for violations and stronger enforcement of existing SNF standards.

A systemic shock is roiling the SNF industry as states shift long-term care delivery from SNFs to HCBS and the aged and disabled are given the choice of self-directing their care to assisted living instead of institutions. MLTSS programs that are efficient will open pathways to assisted living for populations at risk of premature institutionalization and for current SNF residents who do not need to be there. With declining censuses and competition from assisted living homes with lower operating expenses, many SNFs will not survive the transition and be forced to close. The niche in the marketplace for the SNFs that survive in the future will be deriving profits from beds occupied by residents who truly need nursing care and not from hallways filled with residents who could safely reside in community-based care settings.

http://info.nic.org/skilled_data_report_pr

https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/259521/LTSSMedicaid.pdf

https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-improving-nursing-home-compare-april-2019

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/28/health/nursing-homes-occupancy.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/07/health/nursing-homes-staffing-medicare.html