By Jason Bloome

About 13 million low income Americans rely on long term support and services (LTSS) which range from assistance with meal preparation, medicine management and/or help with activities of daily living (e.g. dressing, bathing, incontinence, etc.).[i] For individuals turning 65 there is a 70% chance that at some point in their life they will rely on LTSS.[ii] The population of adults 65 or older will double by 2050: increasing from 47.8 million in 2015 to 88 million. The population of adults 85 and older is expected to triple in the same timeframe: from 6.3 million to 19 million.[iii]

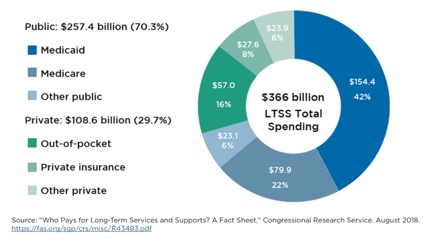

Paying for LTSS for an aging population (one half of Medicaid recipients receiving LTSS are 65+)[iv] is a critical problem facing states trying to control health care expenses. About half of LTSS spending is paid by Medicaid and these costs are expected to increase annually from $113 billion in 2016 to $154 billion in 2025.

Traditionally, states have used fee for service (FFS) to reimburse providers for health care services, but FFS is a very inefficient payment model: health care services are unbundled and paid for separately giving an incentive for physicians and other health providers to provide more treatments because payment is dependent on the quantity of care, rather than quality of care.

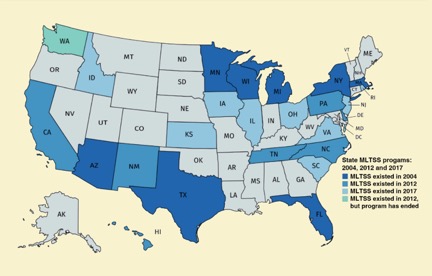

To control LTSS expenses, many states transition from FFS to managed long term support and services (MLTSS) in which states enroll their LTSS populations with contracted managed care organizations (MLTSS plans) to provide health care services. The state determines what the MLTSS plan will receive as a per member per month (PMPM) capitated payment which is recalculated annually. Although the PMPM capitated payment is the same for every enrollee, the amount of care services an individual receives varies on a case by case basis. The PMPM capitated rate is frequently derived, in part, by calculating the total cost of care for individuals in different rate categories (e.g. is the beneficiary receiving LTSS at home or in a skilled nursing facility). Ideally, the capitated premiums cover the costs of care for all MLTSS plan members; with plans spending less money for members who need fewer services and more money for members who need more care. Benefits of MLTSS include cost containment, efficient care delivery, budget predictability for the state and the potential for Medi-Cal costs savings which can be shared between the state, federal government and the MLTSS plan. As of 2017, 24 states use MLTSS with a total enrollment of 1.8 million Medicaid recipients.[v]

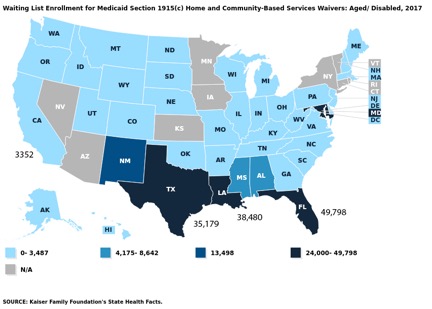

The use of MLTSS provides avenues for LTSS rebalancing from expensive skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) to more affordable home and community-based care services (HCBS) options. Given the choice, most seniors would prefer to live at home or in a community-based care setting rather than in an institution but available slots for HCBS is limited in many states. In 2017 there were 49,798 aged/disabled people on the HCBS waitlist in Florida, 35,179 in Texas, 38,480 in Louisiana, and 3,352 in California.

Increasingly, states which have MLTSS use In Lieu of Services (ILOS) to reduce HCBS waitlists by giving MLTSS plans the flexibility of promoting community-based alternatives instead of institutions for members who are “nursing home eligible” but able to receive care in care settings “in lieu of” nursing homes. Some states allow ILOS to pay for care in assisted living homes which, as “authorized expenses”, are factored into the annual PMPM rate calculations.

California recently published their Medi-Cal Healthier California For All Proposal (MHCFA) which envisions the state eventually transitioning all LTSS recipients to MLTSS. One component of the MHCFA proposal allows care in residential care facilities for the elderly (RCFE) to be considered authorized ILOS expenses: welcome news for low income families struggling to find affordable care housing for aged family members when the only state program that currently allows Medi-Cal to pay for assisted living, the Assisted Living Waiver, has a 1-2 year waitlist for community referrals.

The use of ILOS to pay for community-based care will help dismantle hospital discharge barriers frequently encountered by social workers and case managers when SNFs are reluctant to accept short term stay patients funded by Medicare (which pays a high daily rate) who risk become long-term residents on Medi-Cal (which pays a low daily rate).

ILOS also offers the tantalizing prospect for SNF transition for the many LTSS residents in SNFs who could safely reside in community-based care homes. AARP/SCAN estimates at least 10,000 LTSS recipients in SNFs have low level care needs which could be met by community-based care settings.[vi] Transitioning even a small part of this population to RCFEs would generate enormous Medi-Cal cost-savings which could be shared between MLTSS plans, the state and federal government.

In addition, ILOS will provide SNF diversion pathways for some In Home Support and Services (IHSS) recipients who exit the program every year to go to SNFs. In 2017-2018, 5,112 IHSS recipients (or 7% of the IHSS recipients) exited the program to move to SNFs[vii]; many, if given the choice, could safely be diverted to community-based care homes.

The state can accelerate LTSS rebalancing by offering fiscal incentives and/or bonuses to MLTSS plans that successfully develop SNF diversion/transition programs. Establishing a public database that tracks the progress for SNF diversion/transition by individual MLTSS plan would allow the state to track Medi-Cal cost savings, give consumers an insight into which plans have the most progressive programs and foster competition between MLTSS plans.

Jason Bloome is owner of Connections –

Care Home Referrals, an information and referral agency to care homes in

Southern California. More information at carehomefinders.com.

[i] Vivian Nguyen, “Long-Term Support and Services” (Washington: AARP Public Policy Institute, 2017), available at https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017-01/Fact%20Sheet%20Long-Term%20Support%20and%20Services.pdf.

[ii] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “How Much Care Will You Need?”, available at https://longtermcare.acl.gov/the-basics/how-much-care-will-you-need.html (last accessed March 2019).

[iii] PHI, “Understanding the Direct Care Workforce,” available at https://phinational.org/policy-research/key-facts-faq/ (last accessed February 2019).

[iv]MACPAC, Medicaid and Chip Payment Access Commission, “Who uses Medicaid and long term support and services?”: https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/who-uses-medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports/#:~:text=

[v] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Medicaid Home-and Community-Based Services: Selected States’ Program Structures and Challenges Providing Services” (Washington: 2018), available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694174.pdf.

[vi] 2017 AARP/SCAN California LTSS Report Card: http://www.longtermscorecard.org/databystate/state?state=CA

[vii]California Department of Social Services, Executive Summary In Home Support and Services Resident Characteristics for FY 2017/2018, p. 15: https://www.cdss.ca.gov/portals/9/acin/2019/i-22_19_es.pdf