First published on EssyKnopf.com.

Throughout your social work career, all of us will be asked to do the seemingly impossible.

Whether working with clients in therapy to repair psychic injuries, or campaigning for social equality, such feats depend upon a set of specific—but surprisingly mundane—skills.

While some of these skills could certainly apply to other professions, others are specific to the nature of social work, and the demands it makes of us not just as professionals, but as human beings also.

One obvious example of this is the “use of self” in a clinical setting. From time to time, social work clinicians are called upon to appropriately self-disclose.

The openness and authenticity with which we present our humanity can go a long way to facilitating our client’s personal growth and achievements.

Serving others in such a fashion, however, requires we first have some ability to self-regulate—one of the hallmarks of emotional intelligence.

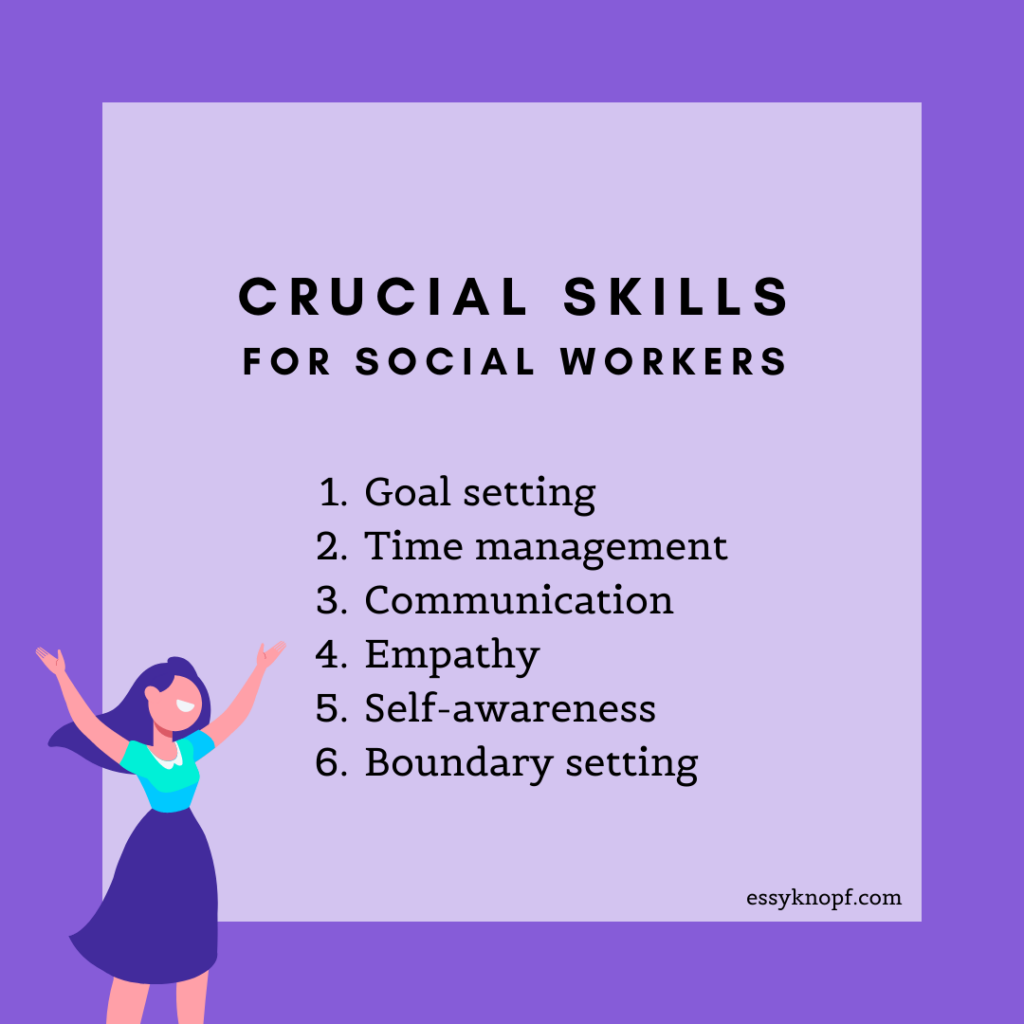

Here are some top skills I believe can help you on the journey towards becoming a better social worker.

1. Goal setting

The only way we can ever get to where we are going is by first clearly defining our destination. This is where S.M.A.R.T. goals come in.

S.M.A.R.T. stands for five categories: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

This goal tracking system helps break often vague objectives into concrete plans with easy-to-follow steps while accounting for any contingencies and obstacles.

The only way we can ever get to where we are going is by first clearly defining our destination. This is where S.M.A.R.T. goals come in.

S.M.A.R.T. stands for five categories: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

This goal tracking system helps break often vague objectives into concrete plans with easy-to-follow steps while accounting for any contingencies and obstacles.

Sure—the level of detail demanded by S.M.A.R.T. goals can often feel mentally taxing—but don’t let this stop you from using them. S.M.A.R.T. goals exist to help you ultimately work smarter, not harder. Simplify the process by starting with a free S.M.A.R.T. goal planning spreadsheet. Set a maximum of three goals.

Once you’ve decided upon the tasks that are necessary to fulfill them, it’s time to deploy skill number two…

2. Time management

For those of us already time-poor, the very idea we should try to wrangle order out of our already packed day is enough to evoke dread. The following two-step process will go a long way to dispel that feeling.

Using the list you generated from skill number one, begin by organizing each task in order of priority:

1. Prioritize your to-dos

Create a rank-ordered to-do list by sorting each task into the following order:

- Urgent and important (do first)

- Not urgent but still important (schedule)

- Urgent but not important (delegate)

- Not urgent and not important (don’t do)

Action each step accordingly. Any item with a #4 ranking can simply be deleted from the list.

If you’re in any way confused by this method, consider using an Eisenhower Matrix (here’s an array of free templates).

2. Schedule

Anything that needs to be scheduled should be recorded in your calendar. If you use a service that syncs across all your devices (such as Google Calendar or Apple iCloud Calendar), all the better.

Next, set reminders so you won’t miss your commitments. I personally prefer to set at least two reminders, one via email and one via instant notification.

Most of us are usually within arms’ reach of our computer or phone, so this can be a great way of ensuring we stay on track.

3. Communication

Communication can play a vital role in connecting, building bridges, and facilitating positive change. This is no less the case during our social work careers.

Whether it’s verbal, written, or visual, good communication is always a question of clarity.

Be direct and succinct, then elaborate, if required. Avoid drowning the receiver with information. Do away with round-about explanations. Make your requests explicit.

Also, it helps to follow these basic rules of thumb, borrowed from a classic book on personal effectiveness, How To Win Friends & Influence People:

- Be friendly

- Respect other’s opinions

- Do more listening than talking

- Try to take others’ perspectives

- Sympathize with their ideas and desires

- Be quick to admit your errors

- Avoid arguments, criticisms, condemnations, and complaints

Always try to put yourself in the shoes of your communication partner. Consider the reaction your words may trigger before speaking.

Finally, collaborate by communicating your projected timelines to relevant stakeholders.

If you think you’re going to miss a deadline, let them know and negotiate a revised due date.

Writing that extra email may feel burdensome, but know that others will always be thankful you kept them in the loop.

4. Empathy

Empathy is the ability to understand and share others’ feelings. It is the glue that holds individuals—and society—together.

Expressing empathy may come naturally to some, whereas for others, it may need to be developed.

Listening attentively is one way we can practice empathy. We can start with body language. By making regular eye contact, we convey we are interested in what the other person has to say.

Uttering “mmhmm” or nodding and shaking our heads are some popular verbal and nonverbal cues commonly used to show one understands and cares.

These responses are also examples of furthering responses, which are the equivalent of asking the speaker to tell you more.

Reflection responses go one step further by addressing both the content of messages and the emotions with which they are expressed.

Our goal when offering reflection responses is to mirror what we, the listener, think we are hearing. “So what I think I’m hearing from you is…”

When we use reflecting responses, we are checking that we have correctly understood whatever has just been communicated to us.

We can also try to summarize or paraphrase our communication partner’s words in a thoughtful and respectful way.

There will be times when our partner responds with, “Actually…” and goes on to tell us how off-base our interpretation was.

Know that misunderstandings are par for the course. What matters most is our willingness to keep working with our conversation partner to get on the same page.

5. Self-awareness

Emotional Intelligence author Daniel Goleman defines self-awareness as ongoing attention towards, observation, and investigation of one’s internal states.

To be self-aware therefore means to be “aware of both our mood and our thoughts about that mood.”

We typically cope with and respond to our emotions in one of three ways:

- Becoming engulfed: Being completely taken over by our feelings.

- Practicing acceptance: Doing nothing to change our moods, even when they cause distress.

- Staying self-aware: Mindfully managing emotions and refusing to ruminate on negative feelings.

Whatever your chosen social work career, acceptance, or engulfment can open us to the possibility of countertransference.

Clinicians who fail to reflect on their feelings in such situations may act out patterns of behavior that damage the therapeutic alliance.

We all have our blindspots. But self-awareness can be actively improved, for instance, by cultivating a mindfulness practice.

6. Boundary setting

Bodies, words, physical space, emotional distance, time, and consequences. These are some categories of personal boundaries, write Boundaries authors Henry Cloud and John Townsend.

A common boundary violation in social work is long hours and high caseloads.

Most of us would agree that our ability to flourish depends upon our ability to keep stress to moderate levels. We also require plenty of time to rest and recharge.

When these two things are denied us, however, it is our responsibility to clarify and assert our boundaries. This may mean saying “no” to taking on more work than we can manage. Or it may mean leaving an exploitative situation.

Should we choose not to, we may otherwise succumb to compassion fatigue and burnout.

Another way we can set boundaries is by choosing to not bring work home. This includes refusing to respond to non-essential communication with colleagues and clients outside of work hours.

Doing this also has the added benefit of safeguarding us against forming dual relationships with clients.

Wrap up

Newly minted social workers are like first-time tennis players, struggling to defend themselves against a volley of balls from a merciless pitching machine.

Faced with such challenges, we may pause to peer into the depths of us our generalist’s toolkit, struggling to find the best—and fastest—solution.

The result may be decision paralysis. Failing to deliver a return may leave us with the figurative black eye of imposter syndrome.

But competency in social work is rarely the product of quick thinking or specialized education alone. It’s also about building and maintaining core skills.

By mastering goal setting, time management, communication, empathy, self-awareness, and boundary setting, we position ourselves not just for social work career success, but for career sustainability also.

By Essy Knopf; visit Essy’s blog to read more of his posts in which he discusses best practices, mental health, being gay, and having autism.